Imagine a world where customers can identify your product instantly by its scent.

The idea may seem ambitious, but several countries now accept smell as valid trademarks. The U.S. has already registered scents like the Play-Doh aroma, bubble gum scent for sandals, the scent of rose oil for promotional services, and even the pina colada scent for a ukulele. Even countries like the UK and EU have also recognised smell marks like the rose scent applied to tyres (in UK) or the smell of fresh cut grass for tennis balls (in EU – now expired)

However, while India has gradually embraced other non-conventional trademarks, such as colour combinations (Cadbury’s purple colour), shapes (Coca Cola bottle or Toblerone chocolate bar), motion (Toshiba moving logo), 3D marks (American Express credit card), or even sound marks (Nokia guitar tune); no smell mark had ever secured registration in India.

But this changed in November 2025 when the Trademark Registry accepted the application of Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd. (a Japanese company) for the “floral fragrance or smell reminiscent of roses applied to tyres” under Class 12 (Application No. 5860303). This decision marked India’s first approved smell trademark and placed the country alongside other jurisdictions that recognise olfactory branding.

BACKGROUND

Sumitomo filed this application in March 2023, and received objections. But unlike every other trademark that requires them to be distinctive and non-descriptive for registration, a smell mark (non-traditional mark), apart from these points, also requires a graphical representation, under Section 2(1)(zb) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, as a part of its characteristics and no one had been able to crack the representation problem until now.

The applicant responded in the normal course, but the matter did not end there. They dealt with multiple notices and hearings and provided evidence of use, proof of its acceptance in other jurisdictions (including the UK Intellectual Property Office), proof of acquired distinctiveness (through third parties), and even 26 examples of acceptance of other smell marks in foreign jurisdictions (United States, United Kingdom, European Union, Australia, and Costa Rica).

WHAT MADE THEIR APPLICATION DIFFERENT?

a) they submitted a scientific graphical representation of their smell mark, and

b) the fact that they applied for the smell mark in relation to tyres, not in relation to perfume, soap, or essence,making it non-functional and arbitrary.

Here’s what the Registry thought of:

a) Graphical Representation: The Registry acknowledged that depicting a smell visually is inherently challenging. However, it is considered that this challenge should not, by itself, deprive the industry (including the essence and perfumery sector) of the benefits of the Act. Since this case involved a rose smell applied to tyres, which presents facts very different from typical fragrance-based goods, the approach also needed to be different.

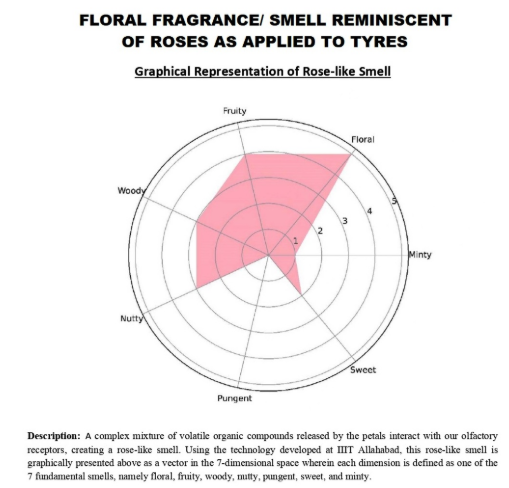

Sumitomo, with the help of Prof. Pritish Varadwaj, Prof. Neetesh Purohit and Dr. Suneet Yadav (3 inventors from IIIT Allahabad) and the support of Mr. Pravin Anand (appointed as amicus curiae for this proceeding), submitted a seven-dimensional vector representation that mapped the smell of rose across seven fundamental scent families (floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet, and minty). In simple terms, they analysed the rose fragrance and broke it down into measurable scent profiles, each with a numerical value based on strength.

The Registry held that the vector shows how the strongest note (floral) would be perceived first, with the others appearing in sequence and fading in order of intensity, with the pungent note being the long lasting. Such representation would allow authorities and the public to determine the precise subject matter of protection. In short, the Registry found this graphical representation to be clear, precise, intelligible, objective, and self-contained, and capable of graphical expression under Section 2(1)(zb) of the Act.

b) Distinctiveness: Distinctiveness is usually shown through a logo, packaging material, or even words. In this case however, the Registry held that the applicant must make a very strong demonstration in order to show distinctiveness.

Here, the arbitrariness of pairing a rose fragrance with tyres made this possible. The Registry observed that when a vehicle fitted with these tyres passes by, the presence of a floral scent would be unexpected. This experience would leave a strong impression because it contrasts sharply with the smell of rubber normally encountered on roads. As a result, a customer would be able to associate the scent with the source of the goods (the Applicant).

TAKEAWAY:

This decision not only opens the possibility of registration of smell marks but also acts as a guide for anyone who wishes to register a smell mark, which includes

a) Ensuring the non-functionality of the smell with the product. In other words smell and its product should not have any relation to each other.

b) Providing a solid scientific graphic representation that shows exactly what the smell is, and how it works, how it affects the consumer and not just a written description.

c) Providing real evidence that people associate that scent with your brand, whether through use, surveys, advertising, or recognition abroad.

If a tyre that smells of roses gets accepted today, it opens us up to many possible trademarks for the future. Erasers that smell of pertichor, or handbags that smell like the ocean breeze. What kinds of potential smell marks do you think will fulfil the criteria ?

Author: Gautam Bhatia, Associate at PA Legal

Thank you for reading our blog! We’d love to hear from you!

- Are you Interested in IP facts?

- Would you like to know more about how IP affects everyday lives?

- Have any questions or topics you’d like us to cover?

Send us your thoughts at info@thepalaw.com. We’d love to hear your